K-Cruelty: Inside South Korea's Largest Horse Slaughterhouse

One-Way Ticket: PETA Investigation Exposes the Tragic Fate of U.S. Racehorses Exported to South Korea

Update: January 2022

After PETA’s investigation, the demand for horsemeat in restaurants and stores plummeted, so officials proposed opening a slaughterhouse to kill racehorses for pet food. Local activists and civic groups succeeded in stopping the plan and joined PETA in demanding a humane system for racehorse aftercare/retirement.

Update: July 20, 2021

PETA exposed that the Korea Racing Authority, in a shameful cover-up, removed all slaughter information from its online horse registry and took down the quarterly slaughter reports from its website.

Update: December 16, 2020

After viewing PETA’s video exposé of the slaughter of racehorses in South Korea and learning from PETA that American stallion Private Vow—who ran in the 2006 Kentucky Derby—was quietly slaughtered for meat in July 2020, The Stronach Group (which had already agreed to stop selling its own horses to Korea) endorsed PETA’s efforts to ban all racehorse sales to Korea.

Update: June 30, 2020

In order to promote the province’s sagging horsemeat industry, Jeju officials announced a new horsemeat certification program for restaurants that pledged not to use meat from racehorses.

Update: January 7, 2020

The Jeju Livestock Cooperative Association (Nonghyup) and three of its employees were convicted and fined for killing horses in full view of other horses, in violation of South Korea’s Animal Protection Act.

Update: October 17, 2019

A Korean federal legislator publicized the issue that meat from retired racehorses is sold in restaurants, even though the animals had been given banned substances that cannot be used in horses killed for meat. He cited PETA’s video of horse Cape Magic, who had been administered phenylbutazone for his injuries less than 72 hours before slaughter.

Update: June 13, 2019

Korea’s top sire, American stallion Menifee, died of a heart attack after being forced to breed despite his worsening heart condition. PETA called for an investigation and released previously unseen, extended footage, including video of one of Menifee’s offspring at the slaughterhouse.

Update: May 20, 2019

Jeju police opened an investigation into alleged violations of the Animal Protection Act. Both the South Korean Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs and the Korea Racing Authority said that they would work to implement a retirement program for racehorses.

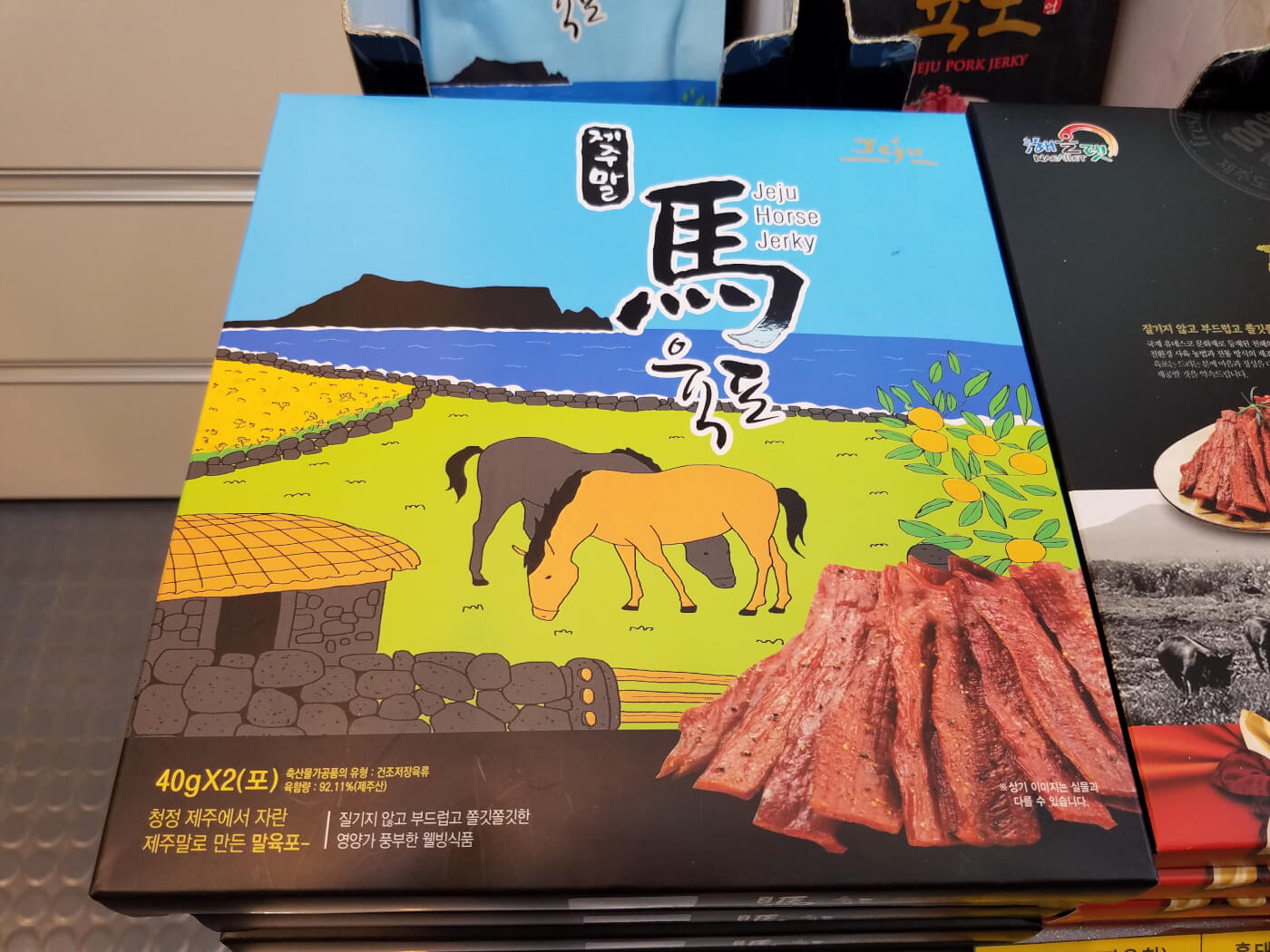

South Korea, where horsemeat restaurants abound, hopes to become a major player in international horse racing—Koreans bet more than US$8 billion annually on races. Just as in the United States, racing takes place primarily on dirt tracks, so the KRA imports hundreds of American horses each year for racing and breeding. While aggressively breeding and bringing in new blood to improve South Korean racing, the KRA discards those horses who get injured or don’t succeed. A KRA official stated in 2018 that of the 1,600 horses “retired” from the racing industry each year, only 50 (or about 3 percent) are deemed suitable for other equestrian uses.

Where do all the rest go? Horse flesh is sold at restaurants and grocery stores, and horse fat or “oil” is used in beauty products. PETA investigators traveled to Jeju, South Korea, to expose the fate of these American horses and their offspring.

Death Sentences

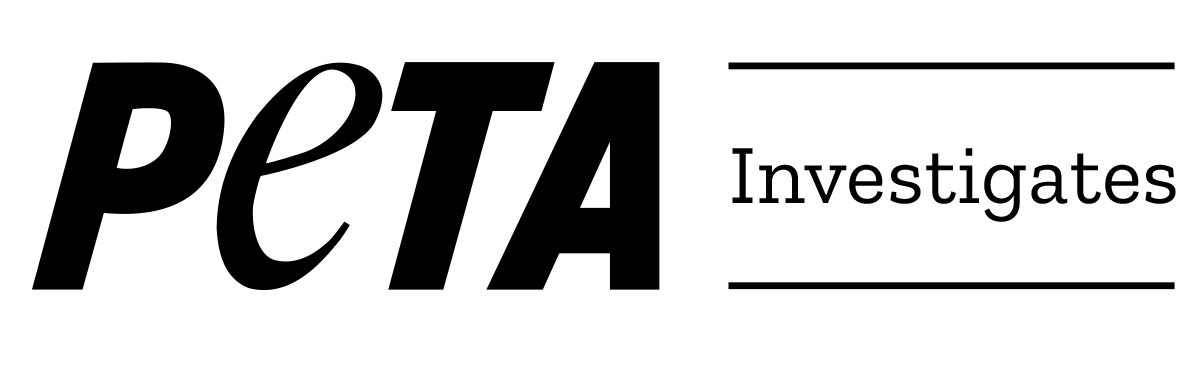

PETA eyewitness investigators captured footage of horses at the largest horse slaughterhouse in South Korea on nine dates between April 2018 and December 2019 and were able to identify 23 Thoroughbred racehorses. One was born in the U.S., 19 had American fathers, and 12 had American mothers. They ranged from almost 2 years old to 13 years old when they were slaughtered, with a median age of 4. Here they are, minutes before being killed:

'Praise the Winner' and Eat the Loser

Seungja Yechan means “Praise the Winner” in Korean—little consolation to this son of American legend Medaglia d’Oro, filmed at the Nonghyup slaughterhouse on May 8, 2018. Freeze brands on his shoulders tipped off the investigators to his identity. Records show that he raced four times and was scratched from his fifth race. Unlike half-sisters Rachel Alexandra and Songbird, who won $3.5 million and $4.69 million, respectively, Seungja Yechan didn’t earn a penny (unless you count the $17 per pound charged for his flesh at the supermarket).

Horse Racing: Not the 'Sport of Kings'—Just Another Livestock Industry

Part of the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA), the KRA tries to gain respect for South Korea as a serious racing nation while also supporting horsemeat consumption. KRA’s chair stated in 2012, “Unlike other livestock raised mostly for eating, horses can meet multiple purposes.… [H]orse meat is good and we will work on ways of encouraging people to eat it in the future.” MAFRA’s recent five-year plan for bolstering the horse industry included promoting “horse meat, cosmetics and other commercial products.” An official said, “Horse breeding will create jobs, such as horse trainers and veterinarians. Horse meat and other products made from horses will be more readily available.”

Some of the horses arriving at the slaughterhouse appeared to have come straight off the racetrack; one of them, Cape Magic, arrived on a Monday morning with a huge bandage on his leg. Records showed that he had raced on Friday in Busan—and he was killed less than 72 hours after finishing out of the money.

Other Thoroughbreds PETA saw at the slaughterhouse were ungroomed, mud-covered, matted, or patchy. After seeing 4-year-old filly Winning Design arrive in poor condition, PETA’s investigators visited the farm that she had just come from.

Owned by a family that also operates a horsemeat restaurant, the farm confined dozens of dirty, unkempt horses to small manure-filled pens and stalls. The stench of feces predominated. One thin horse looked gravely ill—she had an ulcerated eye, hair loss, and sores.

At the slaughterhouse, PETA’s investigators were shocked to see workers beating the horses with sticks to get them to turn around and step out of the trucks and through the doorway. The horses huddled together, clearly panicked, as the men whacked them, including in the face.

Slaughter expert Dr. Temple Grandin watched the footage and concluded, “The handling of the horses during truck unloading was not acceptable. Hitting a horse on the face is abusive. … It is obvious that the people unloading the horses had never had any training in stockmanship.”

Inside the slaughterhouse, workers prodded horses up chutes and into a kill box designed for cattle. An official with the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency told The Korea Observer, “We knock out horses with the same hammer that we use for cows. Things may get a little messy if they do not pass out at the first blow.”

However, beyond the obvious anatomical differences, horses are also generally more nervous and skittish and may jerk away when a captive-bolt gun comes at their head. Inadequately restrained horses make it very difficult for the slaughterer to administer an accurate shot. Even worse, many of the horses arrived in pairs, and PETA’s investigator saw filly Royal River shot right in front of her companion, Air Blade, who had to see her being hoisted into the air. This violated the Korean Animal Protection Act, and PETA and a Korean animal protection group have submitted a complaint about this and the beatings to the District Public Prosecutors’ Office in Jeju City.

Breeding Factories

The KRA’s ambition to raise the quality of South Korean racing has led it to import over 3,600 American horses for racing and breeding in the past 10 years. At the KRA’s massive breeding facility and private farms across the country, stallions are treated like semen machines, made to mount mares multiple times a day in the breeding season. Mares are restrained, washed, tail-wrapped, lubricated, and led to a chest board. Workers apply twitches—rope loops twisted tightly with a rod—to the mares’ upper lips to hold them in place. Others strap breeding boots onto the mares’ back feet so they can’t injure the stallions by kicking. Injuries appeared to be common. PETA’s investigators saw the following:

- American broodmare Catch Me Later, whose left hind foot was so painful that she couldn’t put weight on it so workers couldn’t put a breeding boot on her other foot, was still forced to bear the weight of both a teaser stallion and Colonel John during breeding. She limped badly as workers led her out of the breeding shed.

- Stallion Sadamu Patek’s right eye was grossly swollen, ulcerated, and weeping pus.

- Broodmare Annika Queen’s laminitis (foot disease) was so severe that she could barely walk, but her owners made her nurse a second foal in addition to her own. (Because of her lameness, she wasn’t able to push the other foal away.) A farm manager said that she would be sent to slaughter when no longer needed for nursing.

You Can Help Stop This!

Please demand that the KRA implement a comprehensive retirement plan for unwanted horses in South Korea.